Discover why environmental issues are deeply rooted in social inequality, injustice, and policy—and why real climate solutions must go beyond science to address the human impact.

When we think of climate change or pollution, we often picture melting ice caps or rising CO₂ levels—scientific challenges with technical solutions. But what’s often overlooked is that environmental issues are just as much social problems as they are scientific ones. Across the world, it’s the poorest, most marginalised communities that face the worst effects: unsafe drinking water, polluted air, extreme weather, forced migration, and food insecurity.

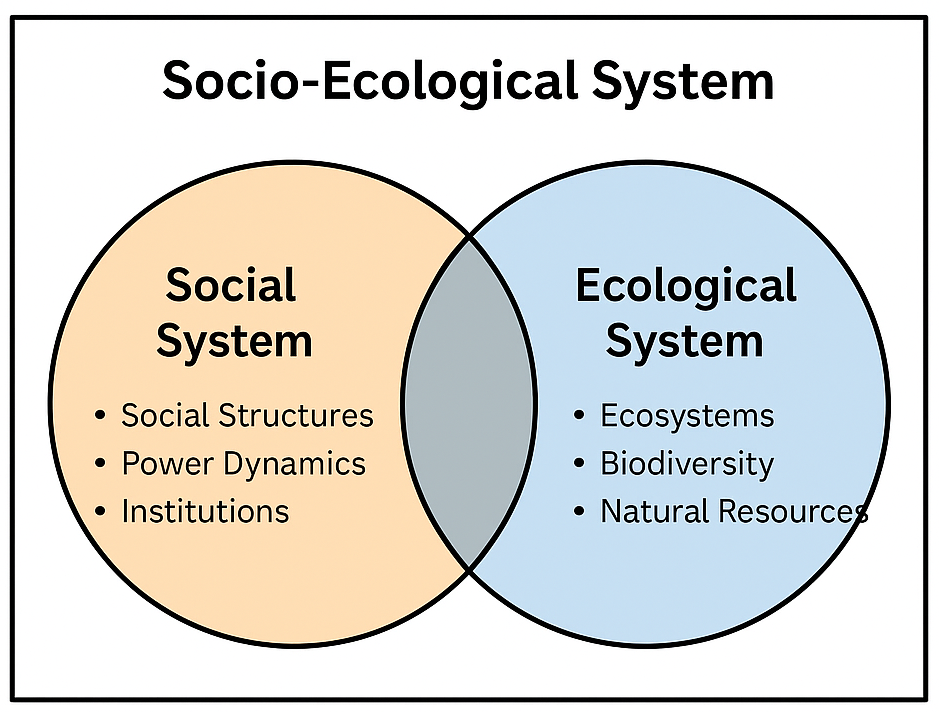

Environmental harm doesn’t occur in a vacuum—it reflects and reinforces existing inequalities in race, class, and power. From environmental racism in urban centres to unequal policy protections in rural areas, the burden is not shared equally. That’s why any effective environmental solution must consider social dynamics, public policy, economic structures, and historical injustice—not just carbon footprints and energy outputs.

In this blog, we’ll explore how environmental degradation affects human wellbeing, why justice and equity are central to ecological solutions, and how social systems drive (and can potentially resolve) environmental crises. From environmental justice movements to the radical vision of social ecology, you’ll see why saving the planet means rethinking how we live together on it.

The Social Fallout of Environmental Change

Environmental harm doesn’t just impact ecosystems—it fractures communities, uproots families, and deepens social divides. When droughts hit, crops fail, and food becomes scarce—not just in theory, but in people’s pantries. When rising seas flood coastal towns, it’s not just infrastructure that’s lost; it’s homes, histories, and livelihoods.

These impacts are not distributed evenly. Around the world, low-income, Indigenous, and marginalised communities are on the frontlines of environmental collapse. They often live in areas more vulnerable to floods, pollution, and resource scarcity—yet have the fewest resources to adapt or recover. For instance, in many developing nations, climate-driven displacement has become a grim routine, while in urban centres, poorer neighborhoods suffer higher rates of asthma and water contamination due to industrial zoning.

Environmental degradation isn’t just a side effect of climate change—it’s a mirror of inequality. It amplifies existing social fractures, punishing those who’ve historically contributed least to the problem. The result? A climate crisis that doubles as a social crisis, demanding solutions that are as compassionate as they are scientific.

Environmental Injustice: Inequality in Exposure and Protection

Not all pollution is created equal—and neither is protection from it. The term environmental justice captures this harsh truth: that some communities are far more exposed to environmental harm than others, and that this exposure is closely tied to race, income, and geography. From hazardous waste sites built in Black and Brown neighbourhoods, to rural communities lacking access to clean water, environmental racism is a lived reality—not a metaphor.

Wealth and privilege act as environmental shields. The affluent can afford to move away from polluted areas, adopt clean energy, or lobby for zoning changes. The marginalised? They’re often left to endure the fallout—literally. This injustice isn’t accidental; it’s the product of policy decisions, historical discrimination, and economic neglect.

But resistance is rising. Across the globe, grassroots movements are demanding a seat at the policy table. From Standing Rock to Flint, from Nairobi to the Netherlands, communities are organising around environmental justice—fighting not just for cleaner air and water, but for fairness, voice, and accountability in how environmental decisions are made.

The Roots: How Social Systems Drive Environmental Destruction

Environmental collapse isn’t just a byproduct of bad choices—it’s the inevitable outcome of systems built on inequality. At the root of today’s ecological crisis lies a toxic cocktail of structural forces: global capitalism, unchecked consumerism, patriarchy, and the lingering shadows of colonialism. These aren’t side issues—they’re the engines driving the destruction.

Take consumer culture. It’s not simply about individuals buying too much, but about an economy that relies on overconsumption to survive. Corporations push endless production, while social status is tied to material ownership—leading to mass waste, pollution, and resource depletion. Add to this the power dynamics of patriarchal and colonial systems, where nature (like marginalised people) is seen as something to dominate, extract from, and discard.

Crucially, we must ask: who benefits from this system—and who pays the price? While multinational companies rake in profits, it’s the marginalised—especially women, Indigenous peoples, and the Global South—who suffer poisoned lands, rising temperatures, and economic ruin. If we want to heal the environment, we can’t just fix carbon levels. We must confront the social values and hierarchies that made environmental harm seem acceptable in the first place.

Policy and Participation: Why Solutions Must Be Socially Grounded

Solving the climate crisis isn’t just about finding the right technology—it’s about building the right society. Too often, environmental policy is crafted in technocratic silos, divorced from the communities it’s meant to serve. The result? Solutions that are efficient on paper but ineffective—or even harmful—in practice.

When policies ignore social equity, they risk reinforcing the very injustices that drive environmental degradation. For example, carbon taxes that raise fuel costs without protecting low-income populations can deepen poverty while breeding political resistance. By contrast, socially grounded solutions—those developed with communities, not just for them—are more likely to succeed long-term.

Successful case studies prove the point. In Brazil, community-led forest management in the Amazon has helped curb deforestation while preserving Indigenous rights. In Denmark, inclusive urban planning has tied climate resilience to affordable housing and social welfare. These examples show that participatory, just policymaking isn’t idealistic—it’s effective.

A greener future depends on more than emissions charts and smart grids. It demands a democratic, inclusive approach to policy—one that sees people not as obstacles to progress, but as its co-creators.

Intersections: Health, Economy, Development, and Environment

The environment doesn’t exist in isolation—and neither does its collapse. Climate change and ecological stressors ripple through every aspect of human development: from healthcare systems strained by heatwaves and disease, to job markets reshaped by green transitions or wiped out by droughts and floods.

Health outcomes are deeply intertwined with environmental quality. Air pollution alone contributes to millions of premature deaths annually, particularly among the urban poor. Water scarcity affects sanitation and child mortality. Meanwhile, economic consequences are mounting—livelihoods lost, supply chains disrupted, homes destroyed by extreme weather events. Education suffers too, as families displaced by floods or fires are forced to withdraw children from school or migrate across borders.

And this isn’t hypothetical—it’s already happening. From rural farmers forced to leave their land to urban workers losing jobs due to climate-driven energy shifts, we’re witnessing a new era of climate migration and economic instability.

The bottom line? Environmental degradation is not a single-issue crisis—it’s a multi-sectoral social emergency. Health, housing, labor, mobility, education—they all live downstream of ecological disruption. To ignore this interdependence is to design policies with blind spots that will only widen social divides.

Why the Scientific Alone Isn’t Enough?

Climate change is measurable. Pollution is trackable. Deforestation can be mapped by satellite. Science offers us the tools to diagnose the environmental crisis with alarming precision—but it cannot fix it alone.

Because behind every carbon emission is a power dynamic. Behind every polluted river is a policy failure. Behind every climate refugee is a story of inequality. To truly solve the environmental crisis, we need more than data—we need social understanding, collective responsibility, and systemic change.

Environmental action must become civic action

This means going beyond carbon offsets or recycling habits. It means voting for climate-just policies, standing in solidarity with affected communities, and holding corporations and governments accountable. It means seeing the climate crisis not just as a planetary emergency—but as a human rights issue, a justice issue, and a democracy issue.

If you’re ready to act beyond the individual, here’s where to start:

- Connect with local environmental justice organisations.

- Support campaigns that prioritise both ecological protection and social equity.

- Educate yourself and others about the human stories behind the science.

Because in the end, saving the planet isn’t about fixing nature—it’s about transforming the systems we live in.

Note: All the images in this article were created using AI tools to help illustrate key ideas. We use these visuals to make the content more engaging and accessible while keeping the message clear and accurate.

Leave a Reply