A deep dive into why modern life is pulling us away from nature—what’s causing the disconnect, why it matters, and how we can restore a healthier bond.

Something subtle yet profoundly consequential is happening across modern society: we are quietly drifting away from the natural world. What was once an effortless part of daily life—contact with trees, soil, birdsong and weather—has become, for many, an occasional luxury rather than a lived reality. This widening gap is more than a cultural shift; it is what researchers increasingly refer to as nature disconnection.

Nature disconnection describes the weakening of our physical, emotional, and psychological relationship with the natural world. It is not merely that we spend less time outdoors—it is that our sense of belonging within nature is eroding. A global synthesis of evidence shows that across age groups, countries, and cultures, human-nature relationships are steadily declining, even as awareness of environmental issues rises. We know more about climate change than ever, yet experience nature less.

Academic work in the field pushes this further. Scholar and ecologist Thomas Beery argues that disconnection is not a simple absence of nature contact, but a complex social and psychological condition shaped by modern living, technology, and shifting cultural expectations. Put plainly: we are not just losing nature—we are losing the part of ourselves that feels at home in it.

This article asks a deceptively simple question: why?

Why, in an era where we understand the importance of green spaces for health and wellbeing, do we spend so little time in them? Why do children now play indoors more than any previous generation? Why do adults scroll for hours yet rarely feel grass underfoot?

The reasons, as we will explore, are layered—urbanisation, technology, cultural change, and policy failures all play their part. The consequences are equally serious: diminished mental health, weakened environmental awareness, and a troubling sense that nature is something elsewhere—a backdrop, not a birthright.

Yet this is not a story of decline alone. It is also a call to action. Understanding how we arrived here is the first step towards reclaiming a connection that humans have relied upon for millennia. The crisis may be silent, but the remedy is not.

How Modern Life Pulled Us Indoors

Urbanisation and Modern Lifestyles – For most of human history, daily life unfolded outdoors. Today, the majority of people live in cities where concrete outnumbers trees and green space is often a planned feature rather than a lived environment. Research shows that urban living dramatically reduces everyday contact with nature, while modern routines—fast commutes, indoor work, tightly structured schedules—leave little time for wandering outside.

Technology and Screen Time Overload – Digital life has not only filled our free hours—it has replaced activities that once happened outdoors. Children now spend more time on screens than playing outside, and adults scroll through breaks that might once have been walks. Empirical studies link higher screen use with lower nature connectedness and reduced motivation to seek outdoor experiences.

Cultural and Societal Shifts – Over the past several decades, unstructured outdoor play has been replaced by organised, adult-supervised activities. Schools increasingly prioritise indoor academics, workplaces keep us at desks, and safety-centred parenting norms discourage children from roaming freely. The result is a culture where time in nature is no longer a default, but a planned event.

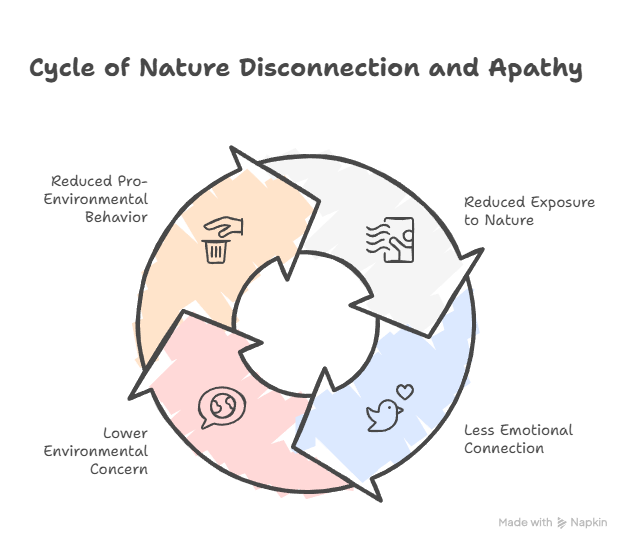

Extinction of Experience and Shifting Baselines – Every generation grows up with less access to wildlife and natural landscapes than the one before. As nature becomes less visible, its absence begins to feel normal. Researchers warn that this “extinction of experience” creates a feedback loop—less exposure leads to less concern, reinforcing disconnection.

Policy and Institutional Barriers – Even when people want more nature contact, access is not equal. Urban planning decisions, socioeconomic inequalities, and poorly protected green spaces mean that many communities lack safe, nearby environments to visit. Policy choices, often unintentionally, make nature harder to reach.

The Consequences: What Happens When Humans Detach from Nature?

Nature-Deficit Disorder – Reduced nature contact has measurable physical and psychological effects. Studies link it to higher obesity rates, increased anxiety and mood disorders, and attention-related issues such as ADHD. Children in particular show lower cognitive development and emotional regulation when deprived of regular outdoor experiences.

Social & Relational Fallout – Technology not only captures attention but also disrupts the face-to-face interactions that once happened outdoors. As screens replace shared outdoor time, families and friendships weaken, and daily life becomes increasingly detached from communal natural experiences.

Environmental Apathy – When people no longer spend time in nature, they lose emotional investment in its protection. Research shows that reduced direct experience leads to lower concern for environmental issues and fewer pro-environmental behaviours, creating a feedback loop of disengagement.

How to Reconnect

Reintegration Strategies – Reconnection begins with access. Research highlights the importance of designing cities that bring nature back into daily life through urban rewilding, accessible parks, and green corridors. Outdoor education programmes and unstructured play opportunities—especially for children—help rebuild early emotional bonds with the natural world, setting lifelong foundations for care and stewardship.

Cultural & Embodied Approaches – Reconnection is not simply a matter of going outside more; it requires cultural and institutional change. Scholars argue that we must shift collective values, rethink education and city planning, and treat nature as a shared cultural asset rather than a recreational accessory. The process is embodied as well as intellectual: people must feel their belonging in nature, not merely understand it abstractly.

Technology as Bridge, Not Barrier – Technology does not have to sever our link to the outdoors—it can strengthen it. Emerging research explores how apps, augmented reality, and digital storytelling can inspire curiosity, guide nature exploration, and make the invisible elements of ecosystems visible to new audiences. Used intentionally, tech becomes a gateway, not a wall.

The Path Back to Belonging with the Living World

The crisis of nature disconnection is not simply an environmental or public health issue—it is an existential one. Our wellbeing, identity, and future resilience depend on restoring a relationship that humans once took for granted. Reconnecting with nature is not nostalgia; it is survival. It demands redesigning cities, rethinking education, and reimagining how we live with the more-than-human world. When people spend meaningful time outdoors, they become healthier, more empathetic, and more likely to protect the living systems that sustain us.

The path back is not easy, but it is available—and it begins with stepping outside.

Leave a Reply